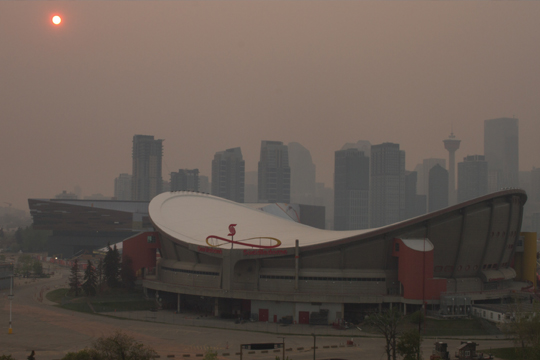

A smoky haze chokes the skyline over Calgary. Unprecedented wildfires have led to high levels of air pollution throughout Alberta and British Columbia.

It is a bleak irony that this series on the effects of climate change has been, at times, delayed because key sources were away fighting its disastrous effects.

Last fall, it was climate experts and others in crisis mode after Hurricane Fiona pummelled the East Coast. More recently, in July, sources on the West Coast battled wildfires on an unprecedented scale. Such fires have erupted across Canada this year — by early June, more land in Canada had burned in wildfires than in any previous year, and all before the usual season for wildfires had even begun.

As usual, Alberta and British Columbia experienced more than their share of destruction. In late July, the Donnie Creek wildfire spanned nearly 6,000 square kilometres, an area that‘s bigger than Prince Edward Island, and the biggest fire in B.C.‘s recorded history. (Wildfires in Quebec and Northern Ontario were also worse than usual this year, and Nova Scotia and New Brunswick joined the beleaguered club with destructive fires.)

Such scenes of climate-related destruction are distressingly familiar in the West. In late 2020, rainfall was so intense in Merritt, B.C., that it changed the course of the Coldwater River that flows through the town. In 2021, Lytton, B.C., was devastated by fire and flood, yet perhaps none of these scenes outdoes the apocalyptic videos of people fleeing walls of fire in Fort McMurray, Alberta, Alta., in 2017 — a fire that was, as a recent New Yorker magazine review of John Vaillant‘s book Fire Weather: A True Story from a Hotter World, put it, “hot enough to vaporize toilets and bend a street light in half.” The Fort McMurray fire was also, the reviewer noted, “the most expensive disaster in Canada‘s history.” It is unfortunately clear that that infamous distinction will not stand for long in our hotter world.

Meanwhile, already this year, Alberta communities such as Edson and Yellowhead County have been evacuated repeatedly due to the encroaching threats, and at time of writing British Columbia was still pockmarked with early-season blazes.

The B.C. government is fighting fire with more funds. The 2022 provincial budget announced approximately $350 million in new funding for the B.C. Wildfire Service (BCWS), the agency that is becoming a year-round service. The government also announced, in the 2023 budget, more than $1 billion in funds to fight the climate change that contributes to the growing fire threat.

The very way that fires are fought has also changed.

“What‘s changed is the size of the fires and how we fight them,” says David Greer, the director of strategic engagement and partnerships with the BCWS, who spent 12 years on the ground fighting wildfires. “Things were very different,” Greer recalls. In the 1990s and 2000s, there was less prescribed burning — literally using fire to fight fire, a practice that‘s been used by Indigenous people for generations. “The tool is used way more now… so when fires do hit they will be less vigorous.”

Crews also spend much more time making forests “more resilient to future fires,” he says, for example, avoiding monoculture when replanting and including flora that is more fire resistant.

“Our operation has grown significantly in mitigation, prevention and recovery,” he says. Such measures become more critical as the social, cultural and financial impacts of fire continue to grow. “A wildfire is not an isolated issue,” Greer says, “it affects all aspects of your life.”

You needn‘t be close to a wildfire to be at risk, as cities and other communities are blanketed by high levels of smoke.

“There‘s definitely been, over the last decade or decade and a half, an increase in frequency of wildfire-impacted air quality,” says Dennis Herod, a data manager with the National Air Pollution Surveillance Network, a partnership between Environment Canada and every province and territory. “As you‘ve probably seen with the most recent fires, the smoke can travel thousands of kilometres.”

Vancouver and other centres can be shrouded in smoke from wildfires outside the province — in Washington, Oregon or California, and even in Russia.

The threat inside the smoke is particulate matter.

“They‘re very tiny,” Herod says. “They can penetrate deeply into lungs and even [into] the bloodstream. During wildfire events, studies have shown a large increase in hospital visits and incidences of asthma and other respiratory aggravation.”

The risk increases as wildfires edge closer to urban areas, which is another worrisome trend. Elderly people are most at risk, especially when smoke combines with higher temperatures such as the “heat dome” that killed hundreds of people in B.C. in 2021.

The provincial government recently announced a $10-million program to buy 8,000 air conditioners for vulnerable and low-income people.

Herod notes that Heath Canada also issues heat warnings that are helpful for older Canadians and those with pre-existing respiratory or cardiovascular conditions. “Heat warnings are designed to help people plan their activities and limit [them] when it‘s higher-risk conditions.”

This double whammy of wildfires and overall rising temperatures is also a threat to iconic industries in B.C. and Alberta. Wildfires challenge B.C.‘s lumber industry and the smoke is trouble for the province‘s wine industry. In Alberta, wildfires are contributing to grasshoppers that are being seen earlier than usual and in greater numbers and are consuming tons of agricultural crops. “If it‘s not one thing, it‘s another this year,” one Alberta farmer told CBC Edmonton.

This creates a domino effect that topples into the province‘s beef industry.

“Our cattle need to eat, and so between grass for pasture and hay and silage, and grain crops for feed, that sector really does impact our sector as well,” says Karin Schmid, the production and extension lead with Alberta Beef Producers. “If there‘s not enough feed resources, that is a significant challenge for us.”

Water is also a worry, Schmid says.

“Some areas of the province are likely doing all right, some areas are really dry. I have some concerns about what that looks like for this year and for future years because we rely quite heavily on snowpack and runoff from snowmelt to fill dugouts for water for cattle, and to recharge that soil moisture. If we don‘t have that runoff in the spring, if there‘s hasn‘t been a lot of snow, then those spring rains become even more important.”

Farmers are keenly aware of their role in protecting the environment, Schmid says. Beef production accounts for 2.4 per cent of Canada‘s greenhouse gas emissions, she says, and over the past 30 years, farmers have reduced emissions by 15 per cent while they‘ve produced the same amount of beef using 17 per cent less water and 24 per cent less land.

“We see lots of evolution in the ways that farmers and ranchers try to steward the land for themselves, but also for future generations. A big part of that is learning to deal with some of these climate impacts.”

The damage from wildfires, and other effects of climate change, reach out into the Pacific Ocean, threatening marine life. Skin diseases affecting orcas off the B.C. coast may be the result of warming waters

Saving sea creatures, and ourselves

The damage from wildfires, and other effects of climate change, reaches from the forests into streams and rivers and out into the Pacific Ocean, threatening some of the West‘s most emblematic wildlife.

Experts at the Center for Whale Research have said in recent news reports that skin diseases affecting resident orcas off the B.C. coast may be caused by warming waters, pipeline projects, agricultural pollution and declining food sources for Chinook salmon.

Those salmon are directly affected by wildfires, says Jay Ritchlin, director-general for B.C. and the western region at the David Suzuki Foundation. Fires cause runoff that damages salmon spawning beds, even as salmon face the same temperature increases that orcas are experiencing.

“The water temperature alone makes salmon much more susceptible to disease, making it very difficult for those iconic salmon to survive and recover, even where we have reduced fishing pressure and tried to improve habitat,” Ritchlin says.

Ritchlin says the same heat wave that killed many people in B.C. also killed millions of sea creatures, and threatens the aquaculture industry that is also beset by rising acidity levels in the ocean that make it difficult for shellfish to form their protective shells.

Ritchlin knows it‘s “very challenging to talk about the human culpability for that when in fact many humans are in danger of their lives.” Yet, he adds, “first and foremost, we have to reduce fossil fuels. We can‘t stop talking about that.

“Folks who work in the oil and gas industry are going to be just as affected as everybody else, and their jobs will eventually become redundant, whether it takes three or four more disasters to get us there, or 10 years or 40 years. What we should be doing is working together to find solutions.”

Older workers should get pensions and “let them retire and live in good health,” while others can be helped with retraining and finding new careers,” he says.

“We‘ve got to get this economy off of the level of greenhouse gas emissions, and we‘ve got to take care of everybody.”